More than three decades after the Montreal Massacre, the anniversary of the shootings remains the occasion for alarmist claims about violence against women and the ritual shaming of men. Such shaming may be satisfying to anti-male ideologues, but it does nothing to prevent future violence and should cease immediately.

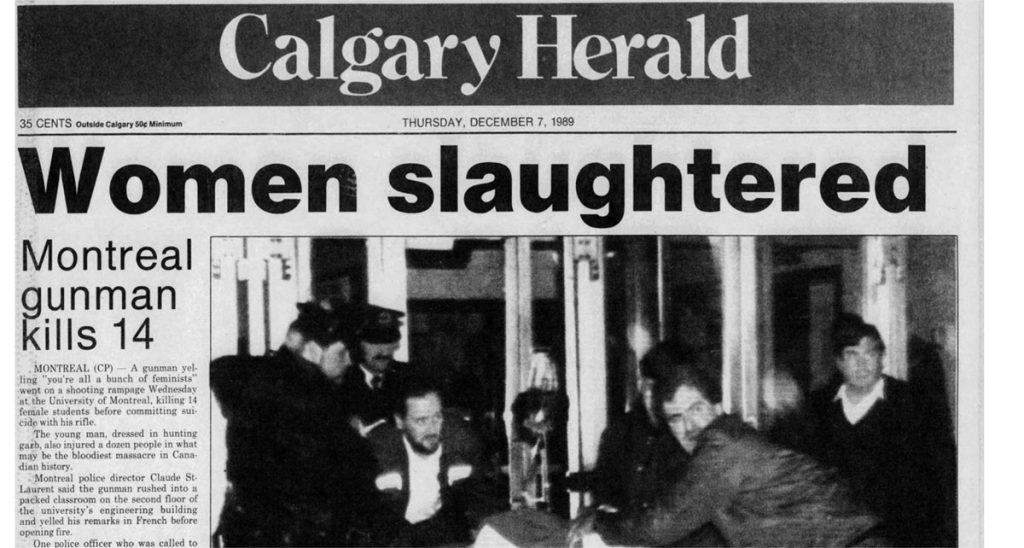

On December 6, 1989, 25-year-old Marc Lépine (born Gamil Gharbi) shot to death 14 women at the Engineering School of the University of Montreal, injuring 10 other women and 4 men. He left a suicide note explaining his rage against feminists, who, he claimed, “always try to misrepresent [men] every time they can.” He also appended a list of particular women he would like to have killed if he’d had time.

Even before the note’s disturbing contents were revealed, most commentators ruled out of bounds the idea that Lépine was mentally ill or that his atrocious act was in any way “incomprehensible” or unusual.

On the contrary, it was held to be representative of a woman-hating society. Feminist journalist Francine Pelletier, writing for La Presse newspaper, set the tone when she described the shootings as a misogynistic warning: “If this is madness, never has it been so lucid, so calculated. […] The message is: there is a price for women’s liberation and the price is death.”

Feminists in general took up the charge: far from being a horrifying one-off, the massacre was a bloody enactment of what was already happening to women every single day. Denise Veilleux, in a letter to Le Devoir, summed up by saying, “Most women know one thing only too well: it’s open season on women all year long!”

Lépine became a symbol for male power and “entitlement.” “What is intolerable for some men today,” wrote Pelletier, “is that some women dare to be unavailable.”

The idea that most women in Canada are brutalized victims is a baseless exaggeration. It is true that men abuse and kill women every year in Canadian society. It is also true that women abuse and kill men every year, a fact that undermines the “gender-based violence” explanation favored by feminists. If women are killed because men have power over women, how do we explain the men who are killed by women? Studies of domestic violence repeatedly show that women participate in hitting, punching, and kicking intimate partners at least as often as men do, and for the same reasons; not infrequently, violent women cause serious harm.

Overall, men are far more likely than women to be homicide victims. In 2018, 484 men, as compared to 163 women, were murdered in Canada. Moreover, men kill themselves far more often than they kill women. These figures are worth pondering not to minimize the horror of what happened in Montreal—or any act of violence against women—but to highlight the capacity of both sexes to cause harm, and our society’s silence about male suffering.

When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau declared on Dec. 6, 2020 that “The safety of women must be the foundation of any society,” it was impossible not to notice the deliberate asymmetry. It’s a national tragedy when women are killed; men’s lack of safety, including their staggering occupational injuries and deaths, is a normal part of life that no leader publicly mourns.

The emphasis on Lépine as a symbol of male power required that the unhappy details of his real life be air-brushed away. We should not be surprised to learn that when he was a child, his home life had been violent and unstable. His father, Rachid Gharbi, an immigrant from Algeria, had a history of psychiatric illness. As Gharbi’s business failed, he became unpredictable and explosive. According to his ex-wife Monique Lépine, he had beaten both her and their son, once “slamm[ing] [his son’s] face so hard the marks were there for a week.”

When Marc was seven, his parents divorced and his father disappeared from his life. Later, Lépine would take his mother’s maiden name (and change his first name to Marc) in an attempt at self-transformation. For three of his teen years, Lépine had a Big Brother, a volunteer mentor, named Ralph, who also ultimately disappeared, possibly due to a conviction for sexual abuse of a boy in his care. At age 17, Lépine attempted to join the Canadian Armed Forces, but was rejected following his interview. It seems that Marc was looking for masculine mentorship and identity throughout his teenage years, to no avail.

He grew up socially awkward, bullied by his peers and considered unattractive because he had acne. Though he was intelligent, he abandoned or failed out of two post-secondary programs, one in pure sciences and the other in computer programming. He applied to study Engineering at the University of Montreal, but was rejected. (I have not been able to ascertain whether the University of Montreal was proactively recruiting female students in the same year it rejected Lépine. ManyEngineering faculties have made no secret of doing so.)

Though Lépine’s hostility towards feminism is undeniable, it did not spring from male privilege, and it is unlikely he ever felt “entitled” to anything.

Still, it made a useful story with which to berate men. For Francine Pelletier, the massacre was not only every woman’s tragedy, but every man’s shame. “The day men start saying that they too are afraid of this kind of behaviour, that it hurts them too, that they don’t want any more of it—that’s the day when things will start to change. Not before.”

Pelletier did not clarify how men were to prevent random attacks like Lépine’s, but the charge that all men were implicated in the violence was one that no man could easily refute, and most didn’t try.

Within two years, December 6th became, officially, “A Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women” (in time The 16 Days of Activism against Violence Against Women). Canadian universities commemorate the event with gatherings and displays, sometimes spread over multiple days and usually attended by university presidents and other top-level officials. Participants make speeches about men “unlearning toxic masculinity” and enact rituals of angry mourning.

Men’s approved role in the anniversary has remained constant: they must accept their shameful affiliation with Lépine and work unceasingly for women’s advancement. At many such commemorations, male students reiterate men’s obligation to stop consenting to women’s oppression.

Such notions are dangerously misleading. Lépine did not kill because he was socialized into machismo or taught to control women. There is ample evidence that men’s violence, like women’s, is caused by multiple factors such as mental illness, addictions, stress, and family of origin abuse.

Sadly, the Montreal Massacre anniversary has become a state-sanctioned occasion for anti-male posturing. For men looking on, the message is clear. No matter how many men die in Canada and globally, whether through suicide or violence or in loving self-sacrifice, there will never be a day to honour them. Even November 11th war memorials, as Lépine indicated in his suicide note, have been “equalized.” While men’s sacrifices for their society are ignored (even while expected), the bad behavior of some few men is magnified out of all proportion and made all men’s responsibility.

It’s far from clear that we can ever “end violence against women,” though the utopian premise conveniently justifies increasingly radical anti-male initiatives. If we are serious about reducing violence, we should start by acknowledging that male victimization is equally tragic, and should seek to understand, rather than demonize, those abject figures like Lépine whose “toxic masculinity” we love to hate.

Janice Fiamengo recently retired from the University of Ottawa, where she was Professor of English. She is the creator of The Fiamengo File and No Joke Janice, 100+ video commentaries on feminism and men’s issues; the full collection of these can be found at Studio Brule. In 2018, she published Sons of Feminism: Men Have Their Say, and is at work on a second volume. She lives in New Westminster, British Columbia, with her husband, poet and songwriter David Solway.